|

Earlier this week I was in a training called Jewish Pathways to Abolition. It began with this question: "When was the last time you felt safe?" The question was provocative and stirred both emotional and physical responses in me. Ironically, rather than thinking of when I last felt safe, my mind raced to all the moments when I have felt unsafe. Some more recent and others in my past. I could feel my shoulders tense, my breathing grew shallow, my mind fogged. After a few beats I reconnected to my feet on the ground and encouraged a long slow inhale and exhale. A longing for safety, for my own and for all people, has been front and center in my own heart these days. Any moment spent reading the news or scrolling through social media sends the message to my own nervous system that this world is an unsafe place. Certainly the news that QAnon is now as popular in the U.S. as some major religions is reason to be existentially concerned. The violence in Palestine continues. And so do the antisemitic chants, memes, and violent attacks in the U.S. and Europe. The longing for safety is not just mine and not just modern, it is also mythic. There is a magical moment in this week's Torah portion, Beha'alotcha. The very last two verses of chapter ten of the Book of Numbers are punctuated (wait, the Torah doesn't have punctuation!?) by the presence of two inverted nuns. It is thought that these backwards, misplaced letters are Greek or Masoretic markings intended to delineate this text in some special way. Many regard the two verses as the remnant of an entire missing book of the Torah.

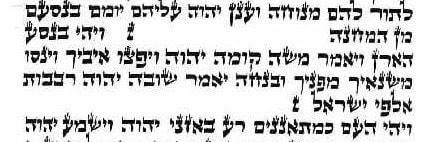

For this reason the rabbinic tradition lifts up these verses and uses them to open and close the liturgical Torah service. (Since it has been a while, you can hear the tune here.) Numbers 10:35 reads: ׆ וַיְהִ֛י בִּנְסֹ֥עַ הָאָרֹ֖ן וַיֹּ֣אמֶר מֹשֶׁ֑ה קוּמָ֣ה ׀ יְהֹוָ֗ה וְיָפֻ֙צוּ֙ אֹֽיְבֶ֔יךָ וְיָנֻ֥סוּ מְשַׂנְאֶ֖יךָ מִפָּנֶֽיךָ׃ When the Ark would travel, Moses would say: Rise Up, Holy One! May those who wish to cause You harm be dispersed. And may those who hate You flee from Your presence! It is incredible to imagine this moment when our ancestors would set out in the wilderness carrying the mishkan on their shoulders. This week, the words landed more tenderly. The desert wanderings of our ancestors and our sacred teachings, the ark itself and those who journeyed with it, were afraid, lest those who hated them cause them harm while they were on their way. Now in the Torah service, after singing these words, we read from the sacred scroll. Then we lift up the Torah, re-dress it, and just as we place it back in the ark we sing the very next verse in our Torah portion, Numbers 10:36: וּבְנֻחֹ֖ה יֹאמַ֑ר שׁוּבָ֣ה יְהֹוָ֔ה רִֽבְב֖וֹת אַלְפֵ֥י יִשְׂרָאֵֽל׃ ׆ And when it came to a halt, he would say: Return, Holy One, You who are Israel's myriads of thousands! Following these words, we sing Eitz Chayyim Hi: "It is a tree of life to those who strengthen themselves in it" (Proverbs 3:18). In this way these two verses have become the portable ark with the entire Torah service nestled within it, a container to hold our ancient stories, the rhythms of our own life and the world around us. Like our ancestors, I too long for those who wish to cause us harm to be dispersed and disempowered. In this moment, I am holding three important personal truths alongside this longing. First, it is possible and necessary for us to condemn antisemitism and be in solidarity with Palestinian liberation. Contrary to the Anti-Defamation League's definition, anti-Zionism is not a form of antisemitism. I feel acutely aware that antisemitic violence and hate speech are strategically used to divert and distract from what is happening in Israel/Palestine. The ADL actually counts critique of Zionism in its "uptick" of antisemitism (more here on that). Second, we experience the prevalence of antisemitic hate speech and violence differently depending on the many identities we hold, including our proximity to state violence and white supremacist violence. And third, I don't just pray that those who wish to cause us harm would disperse on our behalf as Jews, but on behalf of the many identities we hold, the communities we hold dear and everyone to whom they wish to cause harm. The same people and movements that are antisemitic are also anti-Muslim, anti-Black, anti-immigrant, anti-queer and anti-trans. Just as our ancestors trusted the Torah to guide them in the wilderness, we too continually remind ourselves to hold fast to its teachings. We are the descendants of brave, vulnerable, and fearful people. But unlike our ancestors, we are not all alone in the desert. We have the capacity to cultivate lives full of interconnection and interdependence. Our sense of safety is not dependent on scattering our enemies, but on building relationships with our allies. I invite you to consider what is one thing you can do to connect to your community, your neighbors, or yourself to deepen your internal sense of safety. It is a tree of life to those who strengthen themselves in it. May our relationship to Torah, to this community, and to our wide web of interdependence help us stay connected to a vision of solidarity that makes real safety possible. Ken yehi ratzon, may it be so. Shabbat Shalom, Rabbi Ari Lev One of the gifts of Jewish tradition is that it gives us incredible structure and clarity about how to create sacred time. But the lived experience is up to us, to make it our own, to embody it and give it life. The way we live out Jewish tradition is called minhag, often translated as customs.

I want to share with you one of my family's most beloved Friday night minhagim. Every week, after we light the candles and send light out into the world, we dance a full-on hora while we sing "Shalom Aleichem." It started by accident when Zeev was a toddler. We were waiting for guests to arrive and it was taking forever. The food was ready, the table was set, but our friends were still not here. We needed a distraction. So we took out a tiny chair and started dancing, hoisting Zeev into the air like it was a wedding or a B'nei Mitzvah. And as you can imagine, it stuck. Week after week for more than half a decade we have danced a hora, chair and all. Sometimes Shosh and I joke that by the time a big simcha rolls around our kids will say, going up in a chair, "What's the big deal?" But in truth, I don't think that's true. They love it every time. They ask for a second lift as we run out of words and switch to a nigun to keep the dancing going for a few more minutes. And that's all it is - a few minutes - but it's so good and I look forward to it as much as they do. I wonder how old they will be when they are too embarrassed or will we simply need many more adults to lift them year after year? This peak moment is often followed by what I experience as its spiritual corollary, which might best be called "ritual refusal" or perhaps "blessing resistance." Each week I long to extend my arms towards my kids and everyone present, and for us to offer each other what is traditionally referred to as birkat yeladim - the children's blessing. And each week it has been met with a very whiny, "No blessing!" As both the children and grandchildren of rabbis, I'd say my kids have more than earned their right to refuse a blessing. A very reasonable expression of differentiation. To be honest, at this point I have stopped trying, lest they start to refuse any more of the rituals. I settle for the whispers of my own heart, "Be who you are and may you be blessed in all that you are." And then we move on to juice and challah, the sensory experiences that make Shabbat taste like Shabbat. This week, as we watched the unending death toll of human life in Palestine, including a horrific number of children in Gaza, my primal instinct to bless all children with protection and shalom has grown urgent. As of today, more than 230 people have been killed in Gaza, including 63 children, 11 of whom were taking part in a program to help them heal from the trauma of living under occupation. 1,500 Palestinians have been injured and 72,000 Gazans have been displaced from their homes. Twelve Israelis have been killed, including two children. Where is the forcefield of protection for all of these vulnerable people? Earlier this week I watched the video (minute 26:30) of Nadeen Abed Al Lateef, a 10-year-old girl, speaking in front of a bombed out section of Gaza. In her own words: "Do you see all of this? What do you want me to do? Fix it? I'm only 10. I can't even deal any more. I just want to be a doctor or anything to help my people. But I can't. I’m just a kid. I don't even know what to do. I get scared, but not really that much. I'd do anything for my people but I don't know what to do. I'm just 10. I literally cry every day saying to myself, 'Why do we deserve this? You see all of them [pointing to the other kids gathered] we are just kids. Why would you send a missile to kill them?'" Nadeen Abed Al Lateef's words returned me to the words of Congresswoman Rashida Tlaib, the first Palestinian American member of Congress, who courageously spoke these words on the house floor last Thursday: "If our own State Department can't even bring itself to acknowledge the killing of Palestinian children is wrong, well, I will say it for the millions of Americans who stand with me against the killing of innocent children, no matter their ethnicity or faith. I weep for all the lives lost under the unbearable status quo, every single one, no matter their faith, their background. We all deserve freedom, liberty, peace, and justice, and it should never be denied because of our faith or ethnic background. No child, Palestinian or Israeli, whoever they are, should ever have to worry that death will rain from the sky..." This touches the most core longing I have as a parent and human being, and the most ancient and urgent expression of Jewish prayer - the need to pray for peace and protection. A need as old as words. In this week's Torah portion, Naso, we receive the words of the Birkat Kohanim, known in English as the Priestly Blessing (Num 6:22-26). It is considered the oldest blessing in Jewish tradition. (It predates what we now consider our blessing formula of Baruch Atah Adonai... by centuries.) At the heart of the blessing are the words with which the High Priest Aaron is instructed to bless b'nei yisrael, the children of Israel. The Priestly Blessing is a three-fold expression of our greatest longings. A blessing of protection and connection, that culminates in the deep wish for the Holy One to place upon and within each person shalom - wholeness and peace. These past few weeks I have been asking, what is it to pray for shalom/peace? I have received poetic renderings of prayers for peace, written by beloved teachers and colleagues. My real-time response has been a mixture of appreciation, envy, and distrust. I've wondered, why can't I sit and write a prayer for peace? One poem entitled, "It is possible to pray for peace" led me not to my own prayers but to skepticism. "But is it helpful? Does praying for peace get us closer to it?" I do not consider myself so naive as to think that "thoughts and prayers" are a sufficient response to violence and death. (Even CNN thinks that "thoughts and prayers" has reached full semantic satiation, the phenomenon in which a word or phrase is repeated so often it loses its meaning.) But I also fear the moments when I have grown so calloused that there is not a place in my psyche to connect to my deepest longings and the full humanity of all people. The need to pray for peace is so primal that it is the culmination of every single Amidah. It punctuates every Jewish ritual and prayer service. Is it the final declaration of the Mourner's Kaddish. I pray for peace all the time, if not every day. And every time I arrive at the words, "Oseh Shalom bimromav, hi ta'ash shalom - May the wholeness in the sky above, permeate here on earth." I pause and collect my every hopeful, angry, aching dream for shalom and let it radiate and be true and possible, for a moment. But this week it stung with disappointment, and rage, and grief. Many of you have studied with me one my most beloved midrashim, in which the rabbis pontificate about the seven things that were created before the world was created. A version of that midrash exists in this week's parsha (Tanhuma, Naso 11). In this version the list includes "the throne of glory, the Torah, the Holy Temple, the ancestors of the world, Israel, the name of the messiah, and Teshuvah." Much of my own theology has developed from the idea that Teshuvah was created before the world was created. It is the energy of change and transformation in the world. It is what makes healing possible. The creation of Teshuvah is the antidote to a culture of perfectionism that plagues white supremacy culture. Yet this week as I was studying this midrash, I got angry. Like heated, a knot in my stomach, angry. Where is Shalom on this list? Why is that not a necessary mechanism for the world to exist? Yes, we need to be able to transform but we also need to feel whole. We also need to know that death will not rain from the sky. It is not enough to keep Palestine and Israel in our thoughts and prayers. And it is also necessary. Political transformation requires our spiritual imagination. We can't imagine a world that is whole if we cannot connect to it in ourselves. In the words of Marcia Falk, "It is ours to praise the beauty of the world, even as we discern the torn world. For nothing is whole that is not first rent, and out of the torn, we make whole again. May we live with promise in creation's lap, redemption budding in our hands." So this week, I extend my proverbial hands out beyond reasonable or rational reach, to the far corners of the earth, to the deep crevices of my own heart, to anyone willing to receive a blessing (don't tell my kids!). יְבָרֶכְךָ֥ יְהֹוָ֖ה וְיִשְׁמְרֶֽךָ׃ May the Holy One bless you and keep you safe. יָאֵ֨ר יְהֹוָ֧ה ׀ פָּנָ֛יו אֵלֶ֖יךָ וִֽיחֻנֶּֽךָּ׃ May you feel a pervasive sense of connection and know that you are not alone in this world. יִשָּׂ֨א יְהֹוָ֤ה ׀ פָּנָיו֙ אֵלֶ֔יךָ וְיָשֵׂ֥ם לְךָ֖ שָׁלֽוֹם׃ May we experience within us the wholeness and peace that is possible from living in a world that is entirely just. Shabbat Shalom u'Mevorach, Rabbi Ari Lev Deep breath.

This has been a painful week, full of devastating violence in Jerusalem, Gaza, and throughout the region. As we write this, the violence continues to escalate with massive aerial bombings of Gaza, and rockets targeting Israel. While Jewish communities began a new month in anticipation of the festival of Shavuot, Ramadan came to a close with the festival of Eid. Throughout the sacred month of Ramadan, Israeli restrictions on Palestinian movement in the Old City escalated into a military attack on the Al-Aqsa Mosque, the third most holy site in all of Islam. Simultaneously in the Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood of East Jerusalem, Israeli authorities attempted to evict Palestinian families to make way for Israeli settlers. We understand all of this violence to be the result of nearly a century of Israel's systemic oppression, dispossession, and dehumanization of Palestinians. It is overwhelming and heartbreaking. On Wednesday morning, we gathered for a Hallel service to welcome in the new moon of Sivan. There is a deep emotional and spiritual dissonance in singing the celebratory words of Hallel during a time of such gravity and devastation. But among the Hallel liturgy, in Psalm 115 we read: הַשָּׁמַיִם שָׁמַיִם לַיהוָה וְהָאָרֶץ נָתַן לִבְנֵי־אָדָם׃ The heavens belong to the Holy One, but the earth, The Holy One gave to human beings. These words call us into responsibility –– we are entrusted as human beings to care for what happens here, and for one another. The earth is our domain. As we prayed these words, we recommitted to the sacred duties of human interconnection, caring for the land, and all who dwell on it. We, Rabbi Ari Lev and Rabbi Mó, write to you from a place of personal grief and responsibility. For the duration of our tenures at Kol Tzedek we have not directly talked about Israel and Palestine as leaders of this community. We are a congregation where a diversity of opinions and lived experiences are held and embodied. We have censored ourselves out of fear that we couldn't do it in a way that would not cause harm within our community. The challenge to talk about Israel and Palestine is not unique to Jewish communities, though it is particularly fraught. In this moment of crisis, we feel the impact and inadequacy of this silence. We each have our own personal relationships and experiences that we bring to this moment. And we know that you do too. We wanted to take a moment to share from our own hearts with you. We do this knowing that what we share runs the risk of disappointing you, angering you, or betraying your expectations. But we want to share transparently with you, both because it's what allows us to authentically serve as your rabbis, and in order to model the personal sharing we'll need to do as a community in order to talk more directly about Israel and Palestine. I, Rabbi Ari Lev, have spent weeks living in the West Bank and Jerusalem, experiencing both the hospitality of Palestinians and the untenable, pervasive fear of living under occupation. I have run from the gunfire of the Israeli army and taken refuge in the home of a Palestinian elder who fed me plums while I cleared the tear gas from my eyes. I remember playing soccer late at night in the narrow corridors of the Dheisheh refugee camp in Bethlehem, unlearning my own internalized fears of Palestinians that had been transmitted to me as a young American Jew, letting the sounds of Arabic grow familiar and sweet in my ears, and realizing that amidst the terror and chaos, these are people with daily hobbies and hopes, longings for home and connection. I remember growing accustomed to the feeling that it was impossible to plan anything. Days metered by the looming presence of military checkpoints and bomb sirens. On Kol Nidre, when I shared about my experiences on 52nd Street this past summer, when West Philly was occupied by the National Guard in armored tanks, throwing tear gas and shooting rubber bullets. What I did not share is that the only other time I have had that experience was in Palestine. As a white Jew, Palestine is where I learned in my bones about the lived reality of state violence. It is where I learned that I wanted to become an anti-racist. And I, Rabbi Mó, am a granddaughter of four Holocaust survivors who fled to Israel and to Venezuela after World War II. I continue to wrestle with the traumas that brought members of my family to Israel in the early 1950s, where they have continued to rebuild their lives and create a future for themselves. I feel worry, grief, and rage thinking about my cousins and their children, who have spent the week fearing for their safety amidst missiles raining down. And I am in sorrow and agony over the cycles of trauma that got us here –– how my own people came as refugees to Israel, and how multiple generations of Palestinians have been made refugees in that process. In these weeks I have felt my ancestors at my back, and I know that perpetuating a cycle of dispossession cannot truly honor their legacy. I know they longed for a world where I, their descendant, would be safe. I don't know exactly what they would make of me today, a rabbi whose Jewish values taught me to fight for prison abolition, to resist militarized borders, to long for a world without nationalism. Maybe I would be unrecognizable to them. But I know they longed for a world where I would be safe. And in that spirit, I carry on their longing, for everyone to be safe. I long, in their honor, for a world where no one is forced from their home, where no one is bombed in their mosque, where no one who needs refuge is ever turned away. Just as we bring our lived experiences to this moment, we know that you do too. We know that Kol Tzedek members hold strong analyses and convictions about Israel/Palestine. That what happens in the land lives within our own personal narratives in a multitude of ways and that for many people, this is nothing short of questions of life and death, physical and existential. We know that Kol Tzedek members bring different political frames and understandings of the history, causes, and ways out of this crisis. So many in our community have people we love and care about on the ground, Palestinian and Jewish. This is personal and it is political. As we approach the festival of Shavuot, known to the rabbis as zman matan torahteinu, the time of the giving of our Torah, we feel intimately aware that Torah, and religious texts writ large, are used by militaries, nation states, and nationalists to justify the dispossession of people throughout time, and Palestinians at this time. We know that Jewish holidays are marked in Palestine by heightened lockdown and repression. This is antithetical to our understanding of Torah and Jewish traditions. Each year at this time, Jewish tradition returns to the question, "Why was Torah given to us in the wilderness, mid-journey, in a time of tremendous suffering and uncertainty?" A midrash on the first words of this week's parsha, Bamidbar, asks exactly this question. And offers this very personal answer: כָּל מִי שֶׁאֵינוֹ עוֹשֶׂה עַצְמוֹ הֶפְקֵר כַּמִּדְבָּר, אֵינוֹ יָכֹל לִקְנוֹת אֶת הַתּוֹרָה To be able to receive Torah, a person must make themself hefker: ownerless, available, unbounded like the wilderness. At its core, Torah, our sacred teachings, require that we embody a vulnerable and open-hearted posture. To learn Torah, says this midrash, is to open ourselves as widely as possible. This is our gift and our call as a spiritual community. To truly make ourselves available, to carve out space in our hearts for listening and grieving, for learning and transforming. We come to embody true Torah when we are open and available, with each other and in our struggles for justice. In the upcoming Shmita year, the Kol Tzedek board plans to engage in internal reflection and strategic thinking so we can create better communal processes for exactly these kinds of conversations. So that we don't have to default to silence around the hardest issues. May these words guide us: כָּל מִי שֶׁאֵינוֹ עוֹשֶׂה עַצְמוֹ הֶפְקֵר כַּמִּדְבָּר, אֵינוֹ יָכֹל לִקְנוֹת אֶת הַתּוֹרָה We are called to journey into the terrain of our own hearts, that we may merit wisdom, clarity, and deeper understanding. May our study of Torah and our connection to this community cultivate our open hearts and nurture our commitment to ending this violence, and the injustice at its foundation, as we pray for the safety and liberation of all who live in that, and on this, troubled land. Shabbat Shalom, Rabbi Ari Lev & Rabbi Mó www.sefaria.org/Deuteronomy.11.12Every seven years, every cell in the human body regenerates. This fact has always amazed me. I remember thinking on the seventh anniversary of my coming out as trans that every cell in my body is fully me now. When I officiate at a wedding, I often begin by sharing that the number seven represents wholeness and completion. This helps to explain why the ritual begins with seven circles. But what if the significance of seven is less about completion and more about regeneration?

In this moment in time, we find ourselves in the midst of three different cycles of seven. The first of which is Shabbat. The Torah begins with a creation story in which in six days the heavens and the earth and everything in it is created, and on the seventh day the Holy One ceased from the work of creation. This is our first paradigm for the (notably prime) number 7 as a unit of time. The second cycle is the Omer. We are instructed to count the days following the festival of Passover, a period of seven weeks of seven days, for a total of 49 days. And we are instructed that the 50th day, following this period of weeks, we are to observe the holiday of Shavuot (which is fast approaching and begins Sunday evening, May 16). Today is the 40th day of the omer. The third cycle is that of the Sabbatical year, in which we are nearing the end of the sixth year in a seven-year cycle. We receive this teaching in the opening verses of this week's double Torah portion Behar-Behukotai. Leviticus 25 reads: וּבַשָּׁנָ֣ה הַשְּׁבִיעִ֗ת שַׁבַּ֤ת שַׁבָּתוֹן֙ יִהְיֶ֣ה לָאָ֔רֶץ שַׁבָּ֖ת לַיהוָ֑ה שָֽׂדְךָ֙ לֹ֣א תִזְרָ֔ע וְכַרְמְךָ֖ לֹ֥א תִזְמֹֽר׃ But in the seventh year the land shall have a sabbath of complete rest, a sabbath of the Holy One: you shall not sow your field or prune your vineyard. Much like the observance of Shabbat, in which we work for six days and rest on the seventh, we are instructed to work the land for six years and to let the land rest on the seventh. This cycle comes to be known as the practice of Shmita. In fact, the Torah teaches us about this practice three times. Once in Exodus 23, in Leviticus 25, and then in Deuteronomy 15. In the first two occurrences, it describes an agricultural practice in which the land gets to rest. But in Deuteronomy, it actually describes a practice of economic justice in which all debt is forgiven. The word Shmita itself actually means release or letting go, and comes to be equally associated with both agricultural and economic practices. And much like we count the Omer, our Torah portion explains that we should also count the weeks of years: וְסָפַרְתָּ֣ לְךָ֗ שֶׁ֚בַע שַׁבְּתֹ֣ת שָׁנִ֔ים שֶׁ֥בַע שָׁנִ֖ים שֶׁ֣בַע פְּעָמִ֑ים וְהָי֣וּ לְךָ֗ יְמֵי֙ שֶׁ֚בַע שַׁבְּתֹ֣ת הַשָּׁנִ֔ים תֵּ֥שַׁע וְאַרְבָּעִ֖ים שָׁנָֽה׃ You shall count off seven weeks of years—seven times seven years—so that the period of seven weeks of years gives you a total of forty-nine years... וְקִדַּשְׁתֶּ֗ם אֵ֣ת שְׁנַ֤ת הַחֲמִשִּׁים֙ שָׁנָ֔ה וּקְרָאתֶ֥ם דְּר֛וֹר בָּאָ֖רֶץ לְכָל־יֹשְׁבֶ֑יהָ יוֹבֵ֥ל הִוא֙ תִּהְיֶ֣ה לָכֶ֔ם וְשַׁבְתֶּ֗ם אִ֚ישׁ אֶל־אֲחֻזָּת֔וֹ וְאִ֥ישׁ אֶל־מִשְׁפַּחְתּ֖וֹ תָּשֻֽׁבוּ׃ and you shall hallow the fiftieth year. You shall proclaim release throughout the land for all its inhabitants. It shall be a jubilee for you: each of you shall return to his holding and each of you shall return to his family. I would say this is yet a fourth cycle of counting, except that we don't quite know where we are within it or if its lofty visions have ever been realized. What I do know is that we are preparing to enter a Shmita year in 5782. The practices of Shmita -- Release and Regenerate -- will be this year's High Holidays theme and we will have abundant opportunities to learn, engage, and reclaim them. There are a seemingly infinite number of interpretations of Shmita, so many I can hardly choose where to begin or how to define it. Given the proximity to Shavuot, let us begin here. Rabbi David Seidenberg writes, "The whole purpose of the covenant at Sinai is to create a society that observed Shmita... The Sabbatical year was the guarantor and the ultimate fulfillment of the justice that Torah teaches us to practice in everyday life, and it was a justice that embraced not just fellow human beings, but the land and all life... In modern parlance we call it 'sustainability,' but that's just today's buzzword. It's called Shmita in the holy tongue, 'release'—releasing each other from debts, releasing the land from work, releasing ourselves from our illusions of selfhood into the freedom of living with others and living for the sake of all life... This is what it means to 'choose life so you may live, you and your seed after you.' (Deut. 30:19) This is what it means to 'increase your days and your children's days on the ground for as long as the skies are over the land.' (Deut. 11:21)." May we have the courage in all of the small moments to let go and release. And may the journey to Sinai and beyond lead us closer to a realization of this vision. Shabbat Shalom, Rabbi Ari Lev |

Rabbi's Blog

|

Office & Mailing Address: 5300 Whitby Ave, Commercial #2, Philadelphia, PA 19143

General Questions: (267) 702-6187 or [email protected]

Shabbat Services: 5300 Whitby Ave, Commercial #1, Philadelphia, PA 19143

General Questions: (267) 702-6187 or [email protected]

Shabbat Services: 5300 Whitby Ave, Commercial #1, Philadelphia, PA 19143

RSS Feed

RSS Feed